The History of the Flapper, Part 3: The Rectangular Silhouette

Finally, women could breathe deeply when the waist-nipping corset went out of style

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130219102024WomensInstitutessmUnderwear_cropped_470.jpg)

If a woman in the 1920s had a boyish figure and was naturally skinny, she was all set to slip on a slim sheath, a signature look of the 1920s. But if she was plump and curvaceous, she might choose certain undergarments to help achieve the fashionable unisex flapper shape.

The flapper silhouette was distinctive, and if you’re a fan of PBS’s “Downton Abbey,” you’ve seen it in full effect this season: angular (basically rectangular), androgynous, slender and straight. It was influenced by Braque, Picasso, Leger and others artists whose work had hard, geometric forms and visible lines.

Undergarments worn in the 1920s were a steep departure from the waist-sucking, back-arching corsets of the previous decades. Gone was the Edwardian S-curve corset, meant to shrink the waist and emphasize the backside. It was replaced with garments designed to flatten the chest, hips and derriere.

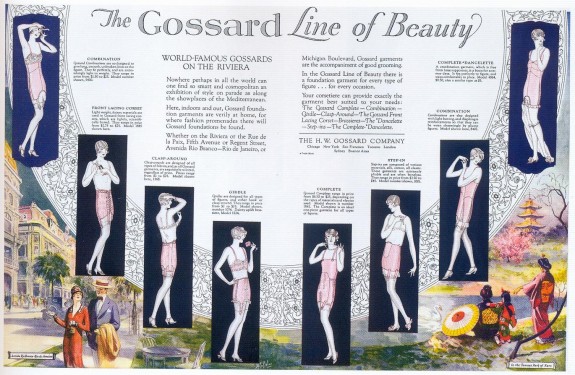

Examples of the figure that women were seeking can be seen in the following ad for Gossard lingerie from 1926. If you didn’t have that shape naturally, and you wanted a Twiggyesque body, that androgynous and iconic look from the 1960s that had its roots in the ’20s, a few underthings could help you along.

Gossard’s line of undergarments, 1926. via Gatochy

One of the more well-known garments of the time was called a step-in. The Gossard ad describes its version as “extremely pliable and often boneless.” These garments, usually made of silk or cotton, were loose, short and lightweight (often with a snap or button closure between the legs). In Flapper Jane, in the September 9, 1925, issue of The New Republic, the writer Bruce Bliven described what a young flapper wore.

Jane isn’t wearing much, this summer. If you’d like to know exactly, it is: one dress, one step-in, two stockings, two shoes. A step-in, if you are 99 and 44/100th percent ignorant, is underwear—one piece, light, exceedingly brief but roomy.

Symington Side Lacer, 1920s. via eBay.

But there were other options besides the step-in. The Symington Side Lacer was pretty much the exact opposite of the 1990s Wonderbra. Once on, you pulled the straps to flatten and minimize the size of your chest, thus more easily slipping into the shapeless, drop-waisted dresses that were in fashion.

The point was to de-emphasize the default curves of a woman’s body that had been exaggerated in previous decades. But, for many women that would mean getting into an elastic tube, a more structured version of today’s Spanx. Freedom from a boned corset allowed women to finally, and literally, exhale with relief (and more easily dance the Charleston).

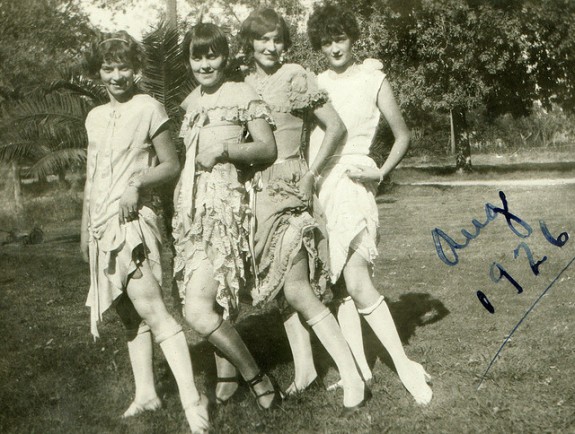

With undergarments came stockings. Forget garters! The trend was to roll your stocking. And with hemlines rising to right below the knee, the chance that someone would catch a glimpse of your rolled stocking, and even more scandalous, your knee cap, was kind of the point. Padded methods increased the girth of the roll so the stockings would become more noticeable, as described in Threaded’s Stocking Series, Part 4: The Rebellious Roll Garters. In fact, a Paramount silent film from 1927 starring Louise Brooks was even named after the phenomenon. And of course, there’s the classic line from the song “All That Jazz” in the 1975 Kander & Ebb musical Chicago, “I’m going to rouge my knees and roll my stockings down,” that solidified rolled stocking as a cultural touchstone as well as what might be an urban legend and sexual innuendo about flappers rouging their knees.

Was that shape-shifting and recalibrating a successful move toward gender equality during those Roaring Twenties? Yes, reducing feminine curves that had been synonymous with an outmoded version of feminine beauty was a direct path toward evening the playing field for men and women. But, the argument becomes cloudy when you consider that women ultimately looked less like men and more like underdeveloped, prepubescent youths.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)